since I’ve posted. I have neglected my introvert workings. Just a brief note here to let you know I’ll be coming back soon, and that I will NEVER use the phrase “the human condition” in any artist statement or to describe my artwork in any way, EVER.

Sarah Jessica Parker’s, apparently. I may or may not go to this casting call tomorrow for a new reality TV show about contemporary art, produced and hosted by Sarah Jessica Parker. It’s quite an application and a lot of work just to go for the experience. I don’t exactly have a TV personality, in fact I believe that while I am generally a nice person, I am also a reserved introvert who might come across a bit bitchy on TV (I’m not a bitch, I just play one on TV!). I might also not be the kind of artist a reality show would want. Not enough flair? And would I really want to be on TV? It actually sounds quite awful. But the spectacle is oh so alluring, Mr. Debord.

It’s hard to stay positive with so much job searching and no calls for interviews, especially when I’m overqualified for most of the available jobs to which I’m applying. Attempting to write a thesis, auditing a class, taking another one, job searching, and thinking about so many possible applications… to the Fulbright, to PhD programs, to MFA programs, to grants, to residencies, to internships… I need an income. I also want to keep moving forward in my thought and my artwork, and the jobs currently available are simply depressing. A good time to apply to grad school again. The PhD / MFA split is especially tiresome, though. I do not fit with either but feel I must choose. Where on earth to apply? Where there is funding, apparently.

Posted in Uncategorized | 3 Comments »

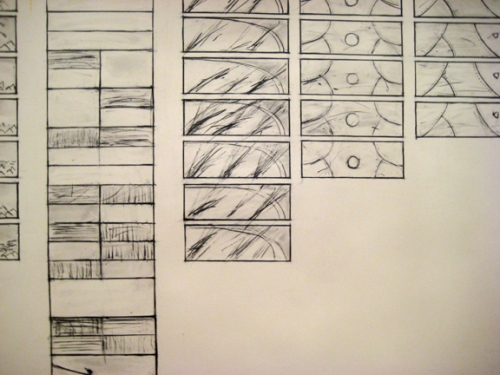

For several years I have worked mainly in the medium of photography, producing large tableau photographs in the manner made popular by Jeff Wall and the Bernd and Hilla Becher school of photographers. The works I made were constructed studio photographs produced with a view camera and were reliant upon metaphor and art historical references applied to contemporary social situations. Rather than continuing to produce stylistically coherent photographic series, in the past two years I began to produce images related conceptually, if not always in style or imagery, functioning as different facets of interrelated conceptual threads. I began to experiment with different media, including drawing, diagrams, painting, and artist’s books, to produce works related to the photographic work.

Currently my practice is in transition. I have become increasingly unsatisfied with making photographic images as well as with using the human figure. I have started to explore constructing objects and spaces and using images, such as pine trees, laden with symbolic references. Certain elements of my practice remain intact, such as the use of metaphor, working in multiples, and using theatrical lighting. I am interested in the correspondence of materials and the concepts and language they invoke, such as using pine plywood to create boxes for dioramas of pine forests, juxtaposed with photographs of forests. Minimalism and post-minimalism have been influential in my new work through taking the viewer’s bodily experience of the objects as the basis for creating the installation space and for engaging with a sense of theatricality. For example, in a recent installation the viewer must walk around the work to view each box; at each possible viewpoint the work faces the viewer, displayed as three little theaters joined physically around a center of light and illusorily through the mise en abyme of mirrors.

Translation is a series of sculptural installations based on the symbolism of forests and pine trees. The title derives from Walter Benjamin’s essay “The Task of the Translator,” in which he describes translation as shooting arrows into the heart of a forest to find the echo of the original text. I am transposing his metaphoric image onto the relationship between representation and referent while retaining echoes of fairytales and mysticism. Wood and pine trees are construction materials and are represented in images and models. The installations involve a deferral or displacement of the original, or perhaps original copies; they are a mixture of the present fake and the absent or constructed referent, forming larger compositions from multiple, similar parts: difference in repetition, sameness in multiplicity, the forest and its copies.

Translation One is a sculpture comprised of three identical pine-birch ply boxes, each placed on a four-foot white pedestal. They are installed back-to-back in a triangle with a light placed in the center of the formation. Each box has a horizontal gap in the back panel, creating an abstract horizon with the central light shining through, and the interior opposing walls have mirrors, creating a mise en abyme. The exteriors have a minimalist aesthetic, but the interiors function as dioramas of miniature forests, facing the viewer as prosceniums. The model pines are held in place by Styrofoam to emulate snow while not hiding the material’s nature. Previously Translation One was installed with two photographs of forests, but in the future it will be installed in a corner, equidistant from two walls covered in custom forest wallpaper. The sculpture will present a bright center in a somewhat darkened room.

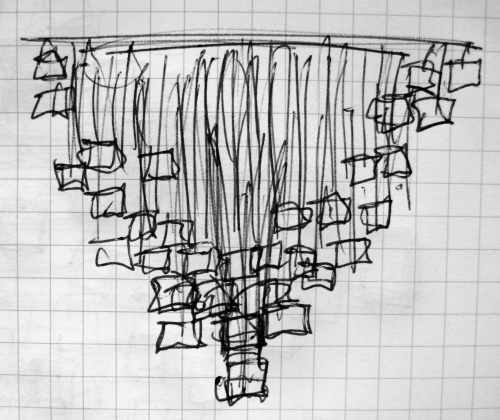

Translation Two is a tightly packed, geometric cone of pine trees, descending from the tallest tree in the middle to the cut tops of trees on the outer rim. They will be secured with wood crosses on the bottom of each trunk, and each trunk will be cut very short with the lowest branches close to the floor. The trees will slowly dry out over the course of the exhibition. The passage of time and scent will be strong components. Fallen pine needles may be swept up to the edge of the cone, forming a rim of dead needles around the work. The work will appear as a dark mass in a white room, with the central tree lit directly from above.

Translation Three is an installation of forest postcards hanging from the ceiling in a spiral cone shape, reminiscent of a chandelier. The room will be dark with minimal spot lighting. Each component piece hanging from the ceiling is comprised of two postcards placed back-to-back, sandwiched between two pieces of glass, secured neatly with black gaffer’s tape around the rim, and suspended from the ceiling with black string. The work will move with airflow, with the glass reflecting light and movement.

Translation One, Two, and Three join the investigation of materials with an exploration of the gallery as a space for metaphor, myth, and dream images. In viewing all three parts of Translation, the viewer will experience changes in light as s/he moves through the galleries, alternating from dark to light and back again. In Translation the symbolism of Christmas trees and references to the sacred through symmetrical compositions and dramatic lighting come together with the capitalism of Christmas tree farms, tourist postcards, and architectural tree models.

Posted in Uncategorized | 2 Comments »

In the Summer Institute I would like to concentrate on a new research project on Claire Démar, a radical feminist and a member of the Saint-Simonian “New Christianity” cult and utopian socialist movement in 1830s Paris. There are few biographical traces of Démar aside from a limited amount of correspondence and two manifestos she wrote between 1830 and 1833. Her writings, Appel d’une femme au people sur l’affranchissement de la femme (A Woman’s Call to the People on the Franchisement of Women) and Ma loi d’avenir (My Law of the Future), are currently published in French but have not been translated. The topics of her manifestos range from calling for an end of marriage and all blood relations to embracing the Saint-Simonian search for the Mother, or Female Messiah, needed to complete the “couple-pope” leadership of the Saint-Simonians. My interest in Démar originated from reading the “Anthropological Materialism” convolute in Walter Benjamin’s The Arcades Project, in which Benjamin collected quotes and information about Démar in relation to messianism and androgyny (which was, in the nineteenth century, conceived in terms of a dualism of male and female genders rather than our current understanding of androgyny as synthesis).

On several levels Performance Studies provides a constructive lens through which to pull together historical and theoretical threads concerning Démar and Benjamin. Many of Benjamin’s seminal ideas were expressed in his dissertation The Origin of German Tragic Drama [Mourning Play], which considered sixteenth to seventeenth century Baroque drama and which stood against notions of historicism and progress. In this work as much of his oeuvre, Benjamin attempted to use what he saw as the unfulfilled potential of history to address present social and political concerns. Looking at this and other works by Benjamin in conjunction with notions of social utopia and Freudian melancholy, gender theory, and performativity, I would like to consider Démar as a tragic, fated figure living in a post-Enlightenment moment when theater had moved from characters determined by godlike fate to possessing historical agency. Though Démar attempted to change the social and political discourses surrounding her position as woman in the aftermath of one of four major revolutions in France in the nineteenth century, she continually wrote about her suicidal fate with the bullet that would someday enter her brain. Beyond applying changes in dramatic form to historical circumstances and beyond Démar’s tragic end with her double suicide with her lover, a historical performative exists in the details of costume (many Saint-Simonians wore their jackets backwards so that another’s aid was required to dress, emphasizing community reliance over self-sufficiency), in the stage of (politically and industrially) revolutionary Paris, in the Saint-Simonian ruminations on gender as alternately essential or non-essential, in Démar’s pseudonym Emilie d’Eymard, and in the utopian search for the Mother (whom the majority of Saint-Simonians believed to be in the Orient, and whom Démar believed to be in America).

The results of my research will take the forms of written, visual, and possibly performative media. The lack of information on Démar may be an advantage in enabling play within the project, in all senses of the word. The Summer Institute will allow me to contextualize and delve into performance as an essential vehicle to making history present.

Another take:

I would like to situate Claire Démar in the lineage of mysticism and cults, as well as utopian socialism, and I am interested in unrealized potentiality, the desire for redemption, and the collapse of the utopian moment. Démar seems to be a wonderful figure to explore the contradictions of myth and progress in historical time (as a historical object in the passage of time), the utopia of America, and the figure of the Mother. For this project I need to gain the breadth and depth of historical knowledge necessary, a better understanding of Benjamin’s cultural theories of modernity, and a better command of the French language to read primary texts by or related to Démar that remain untranslated. I reread her manifestos and correspondence, and then I found an article that translates select passages from her writings. While I understood her writing in a literal way, in reading the select translations I realized I am often missing the subtext and style.

Démar’s letters are melancholic and heart-wrenching, especially when read in light of what the cult leader, Enfantin, wrote about her, but her biography remains a mystery, open for play (literally?). A large problem is posed in representation, as I am troubled by the idea of articulating her image or voice too much, as a bad interpretation of a book into a film. I could detail her situation in time, place, and discourse, yet she will remain a gap or absence (or better yet, an erasure, trace, or palimpsest) in the sketch. Different images come to mind – an empty chair symbolizing the wait for the Mother (as Enfantin had at each dinner table), the bullet of Démar’s dream and her later suicide, the Saint-Simonian costume with the waistcoat worn backwards to button in back, emphasizing fraternal reliance, the blood of patrimony, seamstresses writing “La Tribune des Femmes,” gaps in film and trains symbolizing progress – but everything still seems like flat symbolism. I believe the access to Claire may be through performance, perhaps the project even becoming a performance, seeing her as an ancient or tragic character in a modern, historical narrative, and looking at Benjamin’s Trauerspiel. Any aesthetic often seems absent from Claire’s writing, but metaphor is strongly presented even as she tries to free herself from it.

Posted in Uncategorized | 5 Comments »

Excerpts from Dime-Store Alchemy: The Art of Joseph Cornell by Charles Simic:

“Shadow box / Music box / Pill box / A box which contains a puzzle / A box with tiny drawers, / Navigation box / Jewelry box / Sailor’s box / Butterfly box / Box stuffed with souvenirs of a sea voyage / Magic prison / An empty box” p. 35 (“Matchbox With a Fly In It”)

“Cornell loved Houdini, who was famous for escaping from ingeniously constructed boxes. The boxes had secret trapdoors and exits… That art is called illusionist. Illusionists make it seem… There are two points to make about this: (I) philosophically, illusionism is a theory that the material world is an illusion; (2) illusionism is a technique of using images to deceive. It raises the question of whether perception can give us true and direct knowledge of the world… ” p. 38 (“Birds of a Feather”)

“The little box gets her first teeth / And her little length / Little width little emptiness / And all the rest she has // The little box continues growing / The cupboard that she was inside / Is now inside her // And she grows bigger bigger bigger / Now the room is inside her / And the house and the city and the earth / And the world she was in before // The little box remembers her childhood / And by a great great longing / She becomes a little box again // Now in the little box / You have the whole world in miniature / You can easily put it in a pocket / Easily steal it easily lose it // Take care of the little box.” p. 40 (Vasko Popa, “The Little Box”)

“The work is of wood [continued Viglius], marked with many images and full of little boxes.” p. 53 (“The Memory Theater of Guilio Camillo”)

“He [Camillo] pretends that all things that the human mind can conceive and which we cannot see with the corporeal eye, after being collected together by diligent meditation, may be expressed by certain corporeal signs in such a way that the beholder may at once perceive with his eyes everything that is otherwise hidden in the depths of the human mind. And it is because of this corporeal looking that he calls it theater.” p. 53 (“The Memory Theater of Guilio Camillo”)

“As the curtain goes up we see a forest with tall, fantastic trees. It is night. There’s a moon half hidden by the clouds. Blue mist drifts through the trees. The forest is a place in which everything your heart desires and fears lives.” p. 55 (“The Moon is the Sorcerer’s Helper”)

“Many people have already speculated about the relationship between play and the sacred. The light of reverie, let us note, is a dim light. The near darkness of old churches and old movies is that of dreams. Our memories are divine images because memory is not subject to the ordinary laws of time and space… Images surrounded by shadow and silence. Silence is that vast, cosmic church in which we always stand alone. Silence is the only language God speaks.” p. 57 (“These Are Poets Who Service Church Clocks”)

“There are really three kinds of images. first [sic], there are those seen with eyes open in the manner of realists in both art and literature. Then there are images we see with eyes closed. Romantic poets, surrealists, expressionists, and everyday dreamers know them. The images Cornell has in his boxes are, however, of the third kind. They partake of both dream and reality, and of something else that doesn’t have a name. They tempt the viewer in two opposite directions. One is to look and admire the elegance and other visual properties of the composition, and the other is to make up stories about what one sees. In Cornell’s art, the eye and the tongue are a t cross purposes. Neither one by itself is sufficient. It’s that mingling of the two that makes up the third image.” p. 62 (“The Gaze We Knew as a Child”)

“Every art is about the longing of One for the Other. Orphans that we are, we make our sibling kin out of anything we can find. The labor of art is the slow and painful metamorphosis of the One into the Other.” p. 64 (“Totemism”)

To connect with making the little forest boxes: cabinet and box making to photography (Camera Lucida); tactility of the boxes to the index finger as the true instrument of photography (again Camera Lucida); enclosure, framing, proscenium; the present fake and the absent real/index/referent, minimalism and space/presence; multiplicity and sameness in the forest and in the copies; wood as building material and as represented; analog materials, digital output; original copies, displacement of an original; whimsy, play, reverie, nostalgia.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged Joseph Cornell | Leave a Comment »

I want to think about the desire to know. Specifically I’m thinking about the photo theory seminar I’m taking, and photo theory in general. It seems that there is a divide between being interested in the photograph itself (what it is) and being interested in what we can know through the photograph (what it can do). I think I fall on the ontological side, and my professor on the epistemological side, though of course they are imbricated. Just a thought, but one worth following either to affirm or explode.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged Photography | Leave a Comment »